H5N1: The Monoculture Flu

Having instigated all-out war upon nature via industrial agriculture, humanity is about to experience pandemic blowback the likes of which will make SARS-CoV-2 look like a walk in the park

Foreword

Seeing how I was living in Toronto when SARS1 hit the city (or rather, when it hit a few hospitals) back in 2003, and how on subsequent trips to Australia I was sternly – and repeatedly – asked by customs agents if I’d ever had SARS, you'd be excused for thinking that when official and unofficial stories about SARS2 in China started dribbling out in January of 2020 that I'd have made comparisons with its first iteration. But that's not what happened at all. Because what immediately went through my head was the following:

Oh shit. Is this gonna be H5N1-bad?

SARS-CoV-2 has of course taken its toll on people and society and, with it contributing to what can very well be called a mass disabling event, quite possibly marks the beginning of what some have called "the pandemicine". However, while SARS-CoV-2 has at times crippled supply chains, has killed tens of millions of people (with an initial case fatality rate [CFR] of around 1%-2%, which precipitously dropped with the rollout of first generation vaccines), and has disabled hundreds of millions of others via Long COVID, it's by no means been a civilisation-upending pandemic.

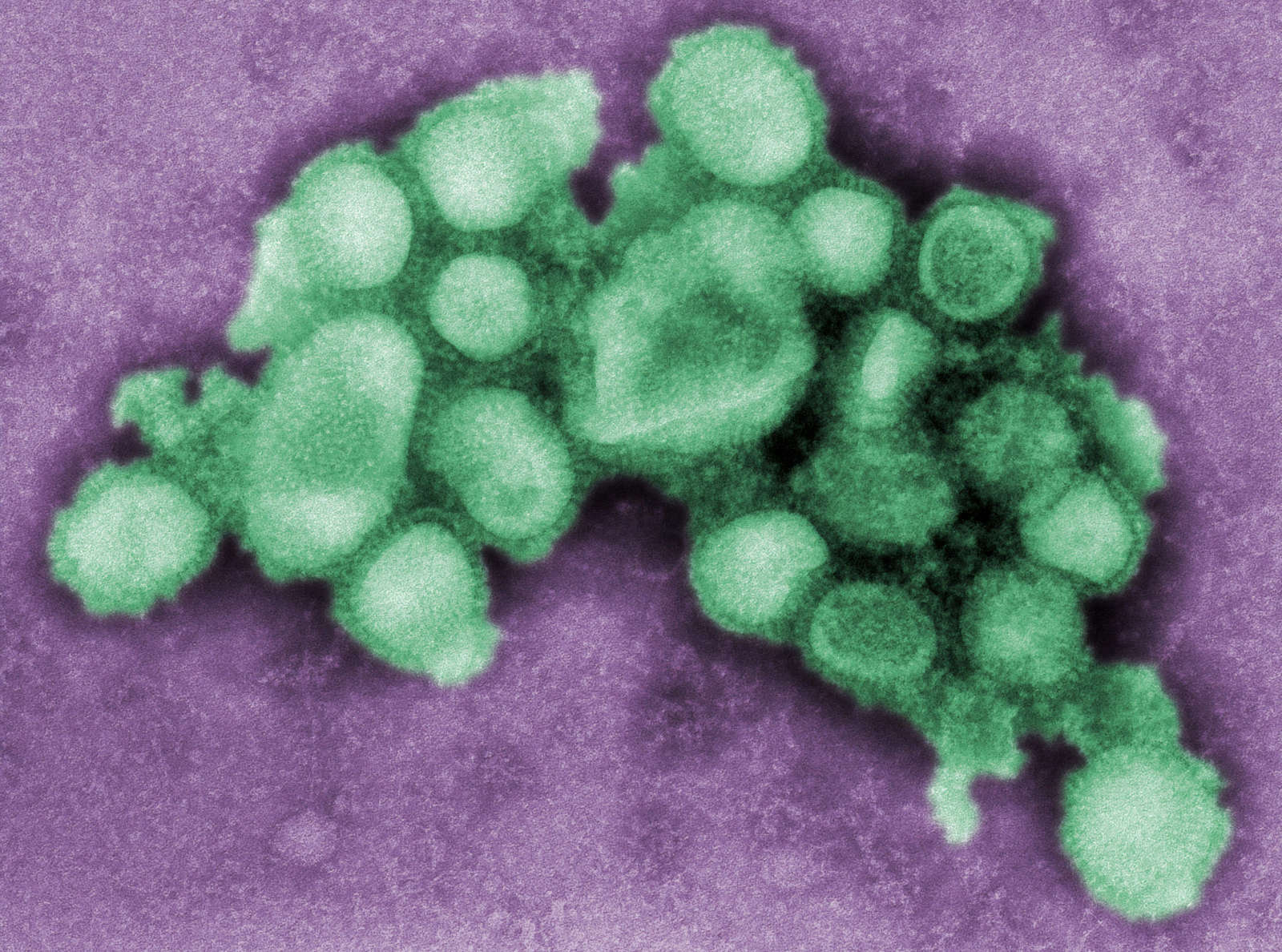

The highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) commonly known as H5N1 (and more broadly as bird flu) is, however, a whole other story. While the virus was first identified in 1996 in farmed geese in Guandong province in southern China (and resulted in a 40% death rate amongst the flock), it was in May of the following year that H5N1 was first identified in humans, in Hong Kong. A three-year-old boy was the first case in the 18-person outbreak, the young boy also amongst the six who died.

While the initial outbreak resulted in a CFR of 33%, the 860 cases of H5N1 that occurred in 19 different countries between 2003 and 2022 resulted in a stunning CFR of 53%. That being so, each of the 860 individual cases had been transmitted from bird to human, human-to-human (even mammal-to-mammal) transmission having never been detected.

Having gone through a binge of pandemic material back in 2008/2009 – during which I devoured a couple of dozen books on the 1918 flu, H5N1, and pandemics in general – and so dedicated a portion of a chapter of the unpublished manuscript which this blog takes its name from to H5N1, this particular virus has been on my mind ever since as a "when" rather than an "if". By default H5N1 became the barometer which I've used to gauge pandemics by (at the time of writing H5N1 had killed 387 people between 2003 and 2008 for a CFR of 63%), and so between the 2020 and 2021 SARS-CoV-2 lockdowns here in Melbourne, and being the collapse guy that I am, you could often catch me saying – with all seriousness – to friends "well, at least this isn't 'the big one'", followed by a quick explanation about H5N1.

Those that didn't know me or my background very well (and who seemingly couldn't imagine anything worse than the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic) generally looked at me as if I was the most stupid person they'd ever met, likely because their "sheltered" understanding of the world genuinely couldn't imagine anything worse than SARS-CoV-2. But for those that had gotten to know me as the go-to guy for delineating what was going on with SARS-CoV-2 and what could be expected next with lockdowns or what have you, the question I was repeatedly asked was "when do you think that'll happen?"

I of course had no idea, and said so, offering little more than "I dunno. To round things off, 2050?"

In August of 2020 I mentioned this upcoming "big one" in a piece entitled "Make Hay While the Pandemic Rages" (in which I alluded to H5N1 with the name I'd given it years earlier, The Monoculture Flu), suggesting that said pandemic might occur at a time when oil supplies were well past their peak and so might be the "once-in-an-industrial-civilisation pandemic" that would be so drastic that an energy-depleted industrial civilisation wouldn't be able to revive itself, thus marking the fast-collapse terminus of industrial civilisation. Regardless, although H5N1 was perpetually on my radar, I didn't seriously expect a double-header with SARS-CoV-2.

That, however, was before December of 2021, when for the first time ever the H5N1 clade known as 2.3.4.4b (which first appeared in China in 2010, albeit as an H5N8 subtype before it swapped its N8 for an N1 in 2020) was detected in North America, courtesy of an exhibition farm in Newfoundland, Canada, where chickens, ducks and geese were found to be infected. 360 birds on the farm were killed by the virus, requiring the remaining 59 to be culled.

Not a month later, January 14th to be exact, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) announced that H5N1 had been detected in a wild duck that a hunter had shot in South Carolina (later confirmed to be of the 2.3.4.4b clade). By late in the year said clade of H5N1 had reached South America, and by October of 2023 had reached the Antarctic region. As stated in Science,

By now, 2.3.4.4b has evolved a niche unlike any HPAI ever seen. Usually HPAI infections die out in a season, but the 2.3.4.4b clade is present year-round in migratory birds. It infects so many species in so many locales that no country's poultry flocks are ever safe.

The only good news to be taken from the ever-worrisome situation was that all detections in mammals were fortunately believed to have been transmitted via birds (be they dead or alive). That, however, all changed in early-2023 when it was revealed that H5N1 (of the same 2.3.4.4b clade) had, possibly for the first time ever, transmitted between mammals courtesy of a mink farm in Spain. With the mammal-to-mammal barrier having thus been broken the crossing of the human-to-human barrier was possibly not too far off, and it looked like "'when', not 'if'" would occur a lot sooner than 2050 (and so not contribute to a fast collapse of industrial civilisation, as there's still plenty of energy left to reboot things no matter how severe a pandemic were to get).

In light of all that (and having personally paid little more than cursory attention to the emergence of monkeypox and the like in mid-2022), in March of 2023, a couple of months after the announcement of mink-to-mink/mammal-to-mammal transmission, I thus began an H5N1-dedicated Twitter/X thread in which I started off by going on the record predicting that H5N1 would go human-to-human in September of 2024, utilizing the #MonocultureFlu hashtag in the second tweet (which I, and only I, have been using since February of 2022).

Gonna call it now: Sept 2024.

Either a highly virulent & immune evasive SARS-CoV-2 VOC, or a highly transmitting human-2-human strain of H5N1. Whichever it be won't really matter preparation-wise, but either way Sept 2024 is the month I'll be aiming to be as ready as can be for.

Update #1: It won't be a SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern, but rather a bird flu. Could actually be H5N1, but for all we know it could be H3N2 or something else entirely. Either way, something like the 1918 flu when people bled from their nose, ears & even eyes.

#MonocultureFlu

2/

Why "Monoculture Flu"? Well, upon the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 I'd entertained the idea of writing an entire book entitled The Monoculture Flu, titled after the term I'd come up with as an outcrop of what I'd written about H5N1 in 2009 in the aforementioned unpublished manuscript (as I mentioned four years ago), material that would be greatly expanded upon in its own dedicated book. (The to-be-written book would include reference to evolutionary epidemiologist Rob Wallace's 2016 book Big Farms Make Big Flu: Dispatches on Infectious Disease, Agribusiness, and the Nature of Science [which still sits unread in my ever-growing pile of to-read books] as well as much else.) The writing of that book is no longer going to happen, and as my unpublished manuscript isn't going to be published in the next couple of months either (meaning the 4,000 or so words I'd written on H5N1 in 2009 would otherwise go to waste if H5N1 does in fact go human-to-human in September), and as previously promised a couple of times, I've decided to publish here on the From Filmers to Farmers blog what I'd written on H5N1 some 15 years ago in the unpublished From Filmers to Farmers manuscript.

What follows is mostly a direct copy-and-paste, inclusive of a couple of footnotes transferred into endnotes (numbers 1 and 24), a couple of deleted sentences, some minor superficial adjustments, and last of all a few added images to spice things up a bit. (Please do excuse what are obviously references to previous portions of the manuscript, as for brevity's sake it was simpler to just leave them as is.)

Without any further ado, here's why I've been anticipating H5N1 for a decade and a half, what it has to do with industrial agriculture, and why I decided to give it the moniker The Monoculture Flu.

The Monoculture Flu

It's safe to say that when problems occur in the monolithic centralized operations we currently have, the scale and reach of devastation becomes so enlarged that they can have not only far-reaching institutional effects but even national and even global ramifications, potentially affecting millions or even billions of people. And it is this very fact that has some people very, very concerned.

Early/mid-2009 saw the emergence of worldwide unease as a pathogenic flu strain traversed the globe from what is believed to be its epicentre in Veracruz, Mexico, host to a hog concentrated animal feeding operation (CAFO). As people across the planet became sick and even died because of the "Swine Flu," fear was building that this might be the outbreak that some have been expecting and dreading.

Jumping a century back for a moment to what is now widely recognized as being an avian flu, the 1918-19 influenza pandemic1 that killed between 50m and 100m people worldwide (equivalent to between 222m and 444m today based on population increase) is often cited as a worst-case example of the pandemic consequences that influenza can entail. Simply put, a flu is a virus that originates in waterfowl such as ducks, geese and gulls (of whom it imparts little to no detriment upon health-wise), and although it is not directly transmissible to humans via the aforementioned, chickens provide biological bridges from which certain strains of the virus can cross over. As described in the journal Science, pigs also have the biological qualities capable of transmitting novel flu strains to humans as "pigs are considered 'mixing vessels' in which swine, avian, and human influenza viruses mix and match… creating… new, hybrid virus[es] that then spread to humans."2

These variant strains are identified by such names as H3N2, H5N3, and so forth (the H and N respectively stand for hemagglutinin and neuraminidase, two viral surface proteins that let the virus infect cells), some of which have been with humans for some time and of which resistance is now common to, while others have not crossed over – and to a certain extent are believed not to be able to – and so pose no threat. The common seasonal flu is an influenza virus that now resides in humans and to which a degree of resistance has been built up against, but whose slight changes (mutations) can still contribute to fatal outcomes amongst the young and the infirm during flu season. Alternatively, a more worst-case scenario occurs when a novel strain crosses the species barrier to which humans have virtually no resistance to.

Ideally (for the flu virus, not us humans), under the right conditions flu viruses naturally take advantage of opportunities that allow them to spread themselves around, be it between birds or between species. This gets a bit tricky for flu viruses as not only do they have to be capable of jumping from one host to the next, but they also can't evolve to the point that they become so virulent that they kill off their host before moving on to another candidate since this would effectively kill themselves off and so "burn out" the virus.

To facilitate the process for flu viruses to develop highly pathogenic and lethal strains that not only jump from bird to bird and bird to human but – this being the big one – from human to human requires either reassortment (whereby a host is infected with both a human-associated flu virus and an avian influenza, genetic reshuffling potentially then creating a deadly new virus) or the right environment and conditions that allow the viruses the opportunities to mutate. What is ideally needed in the latter scenario is a large enough and tightly confined population unable to fend off intruders due to weakened immune systems, all of which allows for a multitude of infections and thus possible mutations. But since people have been keeping pigs and chickens in their yards for thousands of years, why the sudden emergence of highly pathogenic flu viruses that over the past century have killed millions of people at a time?

While it is widely suspected that the virus responsible for the 1918-19 influenza pandemic originally jumped from an animal host to a human on a farm in Kansas, one reputable theory regarding the emergence of its severity, as argued in historian Carol Byerly's 2005 book Fever of War: The Influenza Epidemic in the U.S. Army During World War I, posits that

[The influenza] collaborated with the Great War [...] by producing an ecological environment in the trenches in which the flu virus could thrive and mutate to unprecedented virulence. The influenza virus exploited conditions in military camps, battlefields, and trenches to transform from a common winter ailment dangerous only to the infirm, into a lethal disease that could sicken at least a quarter of all people it came in contact with and could kill even the very strongest. The resulting epidemic in turn impacted the war by striking down millions of soldiers of all armies and spreading disease and death to countries throughout the world. War and disease together thus produced disaster of global proportions.3

Much like the decrepit conditions that chickens and other factory-farmed animals with dysfunctional immune systems live amongst, the "Overwork, overcrowding, exposure to wet and cold, bodily discomfort, loss of sleep, and alcoholism"4 that millions of soldiers were exposed to in the trenches would have similarly wreaked havoc on their immune systems.

Furthermore, along with the deplorable factory farm conditions we most often subject our domesticated animals to, our breeding practices aren't much of a help either. As mentioned earlier about plant breeding, when one breeds for traits such as quick growth, the extra energy going towards bulking up usually comes from sacrificing the traits of immunity, resistance, or capability to deal with various pathogens, infections, and other maladies, essentially resulting in compromised immune systems that get jacked up on now failing antibiotics.

If Veracruz, Mexico, is in fact the locus for the emergence of the somewhat more-than-mild flu that swept the world in 2009 (as another theory is that it emerged in Asia5), it needn't come as much of a surprise. Originally dubbed "Swine Flu" but soon changed to "Influenza A H1N1" (pork producers and non-pork eaters didn't much care for the pig connotations and so the World Health Organization acquiesced to the name change, even though confusion would ensue since much of the seasonal flu is also an H1N1 virus), some have perhaps more aptly called it the "NAFTA Flu".6 (To differentiate Influenza A H1N1 from the H1N1 seasonal flu I'll refer to former from here on in as the H1N1-NAFTA Flu.)

Jointly owned by the already-mentioned Smithfield Farms, Carroll Farms is the CAFO in Veracruz under speculation and is where one can find over 950,000 pigs being raised in a single year. Thanks to lax regulations that emerged after the 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement (the aforementioned NAFTA), the wretched monocultural practices mentioned throughout this book have been encouraged and allowed to proliferate, creating ideal environments for viral mutations.

But as much of a furor has erupted over the 2009 H1N1-NAFTA Flu in pigs, it is not this flu that has had virologists worried for the past decade, but rather a bird flu that emanates from chickens. Although, for example, an H7N3 bird flu strain did emerge in British Columbia in 2004 and resulted in the culling of 19 million chickens, its zoonotic properties (its abilities to jump species) were not very high, and although the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) at first denied any chicken to human transmission7 (whose interests are they looking out for in such dire situations?), the two workers who became infected recovered fine and no further problems ensued in human health.

What does have virologists worried is something like the 1997 H5N1 bird flu (H5N1 having previously been detected in chickens but until then was thought unable to cross over to humans) that broke out amongst humans in Hong Kong, whereby authorities took the quick and drastic action of killing all 1.2 million of the island's chickens as well as 300,000 ducks and geese. New infections ceased overnight, and the virus only ever attained the ability to jump directly from chicken to human, resulting in "only" eighteen people getting infected of which six died – a 33 percent mortality rate.8

Part of what has many people so concerned is that while the 1918-19 pandemic had a mortality rate of less than 5 percent,9 in the ensuing years other (so far small) outbreaks of H5N1 across Asia have had a cumulative mortality rate of staggering 63 percent, killing 387 people between 2003 and 2008.10 If such a pathogenic and lethal strain were to break out – and many experts describe it as a "when" not an "if" – some estimates put the casualty rate at 70 million dead worldwide along with rampant political instability, billions of people avoiding work, and the arduous task of "corpse management".11 In regards to the possible need for "communal burials," the Australian government is concerned about the "multitude of issues in our multicultural [sic] community." As requested by a Health Department spokesperson: "We need all religious societies to respect the fact they may need to be buried communally in mass graves."12

With no help coming from the fact that the majority of us now live in (what are often crammed) urbanized areas, Paul R. Ehrlich and Anne H. Ehrlich point out in their book The Population Explosion that

In short, the human epidemiological environment has become ever more precarious. We are creating a giant, crowded “monoculture” of human beings, which would be at high risk in epidemics even if there weren't millions of people who were especially vulnerable to disease because of their debilitated condition, and even if carriers couldn't zoom around the globe with unprecedented speed.13

Besides reassortment, what I want to reiterate and emphasize is why spot fires of influenza outbreaks occur and why deadly pandemics are feared to occur in significant and highly consequential strength, which is as follows:

- "By breeding for maximum production, the [chicken] industry seems to be breeding for minimum immunity."14

- "[B]irds under stress are much more prone to disease."15 And besides their horrible living conditions and what I've already described, why are they under stress? "The stress associated with the routine mutilations farm animals are subjected to without anaesthesia – including castration, branding, dehorning, detoeing, teeth clipping, beak trimming, and tail docking… [mean that] Never before have microbes had it so good."16

- With sheds packed with thousands of chickens, and areas containing so many sheds that there are hundreds of thousands if not millions of birds in single locations, this means that "The more animals there are to easily jump between, the more spins the virus may get at the roulette wheel gambling for the pandemic jackpot that may be hidden in the lining of the chickens' lungs."17

As Michael Greger, author of the 2006 book Bird Flu: A Virus of Our Own Hatching otherwise puts it,

the industry's continued focus on breeding for the fattest rather than the fittest has resulted in a global monoculture of chickens with built-in immune dysfunction, convenient viral fodder for the initiation and spread of bird flu viruses with human pandemic potential.18

I'm going to venture a bit further beyond my qualifications here. Since various agribusinesses are rarely, if ever, willing to accept culpability for their actions and/or products (they say, for example, that the decreasing effectiveness of antibiotics in people and livestock is due to over-prescribing physicians and overzealous veterinarians, all the while dismissing issues regarding subtherapeutic dosages existent in animal feed), and since chicken industries aren't going to want the word chicken associated with flu and possibly millions of deaths (just as the pork industry didn't like the name Swine Flu), I'm going to save them and their government lobbyists a bunch of time and suggest – in the spirit of the aptly-titled NAFTA Flu – that we call this potentially catastrophic bird/avian/chicken/swine flu for what it really is: The Monoculture Flu. In fact, while Byerly repeatedly stressed in her book the deadly relationship between war and disease and how most wars have seen more men die from disease than from wounds, it could be surmised that The Monoculture Flu would be an outcrop of The War on Bugs, or better yet, the industrial agricultural war on nature.

(If a visual representation is needed for the cause of The Monoculture Flu then I nominate Kentucky Fried Chicken's new Double Down, a bacon and cheese sandwich that uses chicken breasts instead of buns; that is, chicken breasts from monocultured chickens, bacon from monocultured pigs, and to top it all off, cheese from the milk of, I also presume, monocultured dairy cattle.)

Back to the H1N1-NAFTA Flu for a moment, a major opportunity has been lost as attention on prevention has been side-stepped towards mass vaccination programs, an approach that ignores and avoids the source of the problem: factory farming. As Toronto Star columnist Thomas Walkom put it in his article "Pigs, Viruses and Politics" just after the H1N1-NAFTA Flu broke out, "Don't expect [such issues] to dominate the official discourse. The game here is to convince the public that, yes, this near-pandemic is important, but no – other than washing our hands – we don't have to do anything differently."19

Ironically, the faux-pas "prevention" tactics of vaccinations might very well be a crapshoot anyway – and which has only recently become a not-so-paltry $24 billion yearly business for pharmaceutical companies20 – evidenced by a few words by epidemiologist David Waltner-Toews in his 2007 book The Chickens Fight Back: Pandemic Panics and Deadly Diseases That Jump from Animals to Humans:

The flu pandemic could kill a billion people, or maybe just a few dozen. If it is a real killer, by the time we know (the viruses change so fast that we won't know until they are upon us), it will be too late to make a vaccine. By the time the vaccine would be produced, those who are going to die would already be dead.21

Since a 6-month lag generally exists between when a new virus emerges and when a vaccine becomes available,22 one would be justifiably discouraged after finding out that the Canadian government's grand response one year after the initial H1N1-NAFTA Flu has been to expand its vaccination suppliers from one to two.23 To call this a "band-aid" solution would be generous indeed. What it better resembles is a "band-aid on a corpse" solution.

A non-defeatist question to ask then is, Besides stocking up on body bags, antiviral drugs that may or may not work,24 as well as possibly wasting copious resources and efforts on vaccinations that may be one step behind an ever-mutating virus, is there anything we can do to avoid bringing about The Monoculture Flu in the first place? Although it's a bit extreme, Greger thinks there is, and from what I can tell, it's the best – and perhaps only – option we have:

The logical extension of the effective 1997 Hong Kong strategy is to kill off the entire world's chicken flock. Lest this sound too extreme, that's already what happens to most of the world's broiler chickens every six weeks or so. Meat-type chickens have been bred to grow at such accelerated speed that the global broiler flock is essentially slaughtered every handful of weeks and replaced with hatchling chicks. Logistically, killing off all commercial chickens in the world is easy – we have them all locked up. The slaughtering apparatus is in place and already undergoes trial runs about every month or two. If, instead of restocking, humanity raised and ate one last global batch of chickens, the viral link between ducks and humans might be severed, and the pandemic cycle could theoretically be broken for good. Maybe bird flu could be grounded.25

I don't think he means every last chicken in the world, as having pointed out that "Highly pathogenic bird flu viruses are primarily the products of factory farming,"26 Greger also points out that

To reduce the emergence of viruses like H5N1, humanity must shift toward raising poultry in smaller flocks, under less stressful, less crowded, and more hygienic conditions, with outdoor access, no use of human antivirals, and with an end to the practice of breeding for growth or unnatural egg production at the expense of immunity. This would also be expected to reduce rates of increasingly antibiotic-resistant pathogens such as Salmonella, the number one foodborne killer in the United States. We need to move away from the industry's fire-fighting approach to infectious disease to a more proactive preventive health approach that makes birds less susceptible – even resilient – to disease in the first place.27

To allay any confusion, it's important to point out that contrary to what some people are saying, it is not wild flocks of birds that are the cause of any existent or impending bird flu. While yes, wild birds can carry and shed the viruses in their droppings, the viruses often quickly die out when exposed to the sanitizing effects of sunlight and are dehydrated in the breeze.28 And while an outdoor chicken could still get infected, outdoor flocks are often so small that any present viruses have little to no opportunity for mutating to pandemic levels.29 On the contrary, flu viruses can survive for weeks in the wet feces of (dimly lit) factory farm conditions of which chickens walk and sit amongst.30 As just one example, the 2004 British Columbia H7N3 virus emerged not from an outdoor flock but in a chicken shed, from there jumping shed to shed while outdoor flocks were largely left untouched.31

So-called "biosecure" sheds may sound good in theory, but in reality are anything but. Be it due to mice, rats, insects or even human error, such operations actually pose an immense liability to public health as it is virtually impossible to make any facility 100 percent secure from contamination. As author Mike Davis put it in his 2005 book The Monster at Our Door: The Global Threat of Avian Flu, "In an epidemiological sense, the outdoor flocks are the fuse, and the dense factory populations, the explosive charge."32 While some industry proponents are essentially clamouring on about getting rid of the fuses, the explosive charge of industrially monocultured factory farm chicken sheds are getting larger and larger, needing just a spark to set them off.

To allay any confusion, by "industrially monocultured," that does in fact also mean industrially monocultured organic chickens. Author Michael Pollan describes his venture inside one of these industrial organic chicken sheds in his book The Omnivore's Dilemma: A Natural History of Four Meals:

I donned what looked like a hooded white hazmat suit – since the birds receive no antibiotics yet live in close confinement, the company is ever worried about infection, which could doom a house overnight – and stepped inside… [T]hese defenseless, crowded, and genetically identical birds are exquisitely vulnerable to infection. This is one of the larger ironies of growing organic food in an industrial system: It is even more precarious than a conventional industrial system… [and so] everyone keeps their fingers crossed.33

So precarious are these industrial monoculture conditions – be they conventional or organic – that not only are employees often required for "biosecurity" reasons to dip their footwear in disinfectant-filled pans before entering any chicken sheds (where visitors generally aren't allowed entrance at all),34 but some hog barns even require employees to strip and shower upon entering and then don a special set of in-barn-only clothes which get removed upon leaving and washed in the washer inside the premises.35

Taking all these various vulnerabilities into consideration, when we recall Michael Adams' extrapolation that "Canadians believe they [are]… mindful of vulnerability," we really have to examine this a bit. If we say that Canadians are generally mindful of what I have written (which I don't think is the case) and really don't see or even mind the dangers involved, this could only infer a kind of ignorance, indifference, or even masochism. But seeing how Canadians generally aren't mindful of the things I've written about (just see the amount of people dutifully lining up to get their flu shots and then going home afterwards to dine on monocultured chicken or pork for dinner), to think that "Canadians believe they [are]… mindful of vulnerability" is like saying that a person walking in the Australian Outback wearing a lifejacket is mindful of vulnerability, safe in the knowledge that they're not going to drown. A better description of what "multicultural" Canada partakes in and abets – whether or not it is acknowledged or even realized – is large-scale vulnerability.

Afterword

So that's what I wrote about H5N1 in 2009, an understanding that contributed to my simultaneous decision to quit eating monocultured meat as well as other monocultured animal products (of which I eventually extended to all meat in general, an extension that'll last until the day that I can play my part in actually raising and slaughtering the animal(s) I intend to eat). As explained in my post about Australia's 2020 HPAI outbreaks, I do however eat eggs, albeit (non-monocultured) "pastured" rather than "free range" eggs as the latter feel-good term has been appropriated by big business (with the assistance of government officials) in Australia and is now essentially meaningless.

The reason for undertaking all the aforementioned is not only because I've wanted no part (regardless of how small a part it'd be) in directly contributing to – and effectively relishing in – the rise of H5N1, but because I've ideally also wanted no part in reaping the consequences of what H5N1 will all but certainly one day unleash upon humanity. (As stated in the post linked to above, "the countdown to the Monoculture Flu – avian leakage – is on".)

Will it actually "unleash"? Well, as I pointed out near the beginning of this post, in March of 2023 I made the prediction that H5N1 would cross the human-to-human barrier in September of 2024, a year and a half henceforth. Having kept up with that H5N1-themed Twitter/X thread, when it came time to post the thread's 100th tweet a week or so ago I made a more detailed prediction: September 2nd, a month and a half henceforth.

That being said, I make no predictions as to how fast H5N1 will bust out of the gates. If you've read John M. Barry's 2004 book The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Plague in History (which I did 15 years ago, and which I highly recommend reading) you'd be aware that the 1918 H1N1 strain originally started off rather mild. Although nobody's 100% certain what exactly allowed for it to achieve its devastating effects, supposing, as Byerly posited, that the highly inhospitable trenches of WWI played a part, it's worth noting that courtesy of Russia's 2022 invasion of Ukraine...

...they're back.

No doubt the conditions that Ukrainian soldiers find themselves in are nowhere near as horrendous as those that allied soldiers found themselves in during WWI, nor are the trenches anywhere near as crowded. Nonetheless, the return of (sometimes water-logged) trenches to the European continent can be seen to exist as a reminder that we sometimes seem hell-bent on failing to learn from previous mistakes.

But we can learn, which is exactly why I wrote that "Make Hay While the Pandemic Rages" post back in August of 2020, and which is why I subtitled it "In other words, treat COVID-19 like a dry-run for the upcoming 'big one'". Because yes, the "big one" may very well be upon us, and what better way to prepare for it than by looking to our still-fresh experience with SARS-CoV-2 to imagine how we might prepare for a pandemic potentially ten times worse, potentially a hundred times worse.

More to come soon, here on FF2F, about H5N1.

Sounds of the Pandemicene, with Fanfare Ciocărlia

Having quit eating industrial meat roughly 15 years ago upon learning about H5N1 (and then rather unsurprisingly seeing not even a hint of a broad-based move away from such food in the ensuing time) and then watched with amazement the unprecedented spread of H5N1 in wildlife and then monocultured animals over the past two and a half years, paying witness to all this is akin to watching a slow-moving train wreck. Which is exactly how I described it earlier this year in that H5N1-themed tweet thread.

Slow-moving-train-wreck-of-a-pandemic it is, what could be more fitting for this installment of "Sounds of the Pandemicene, with Fanfare Ciocărlia" than an eerie song that could easily be mistaken for the sound of a train slowly pulling out of a station, gradually picking up speed as it heads towards its calamitous destination? That being so, as the chances are that H5N1 will not only escape from a (monocultured) CAFO, but escape from a (monocultured) CAFO in the US (perhaps somewhere in the state of Maryland?), here's Fanfare Ciocărlia playing its train-wreck-in-slow-motion song "Escape from Baltimore".

"Escape from Baltimore" can be found on the album "It Wasn't Hard to Love You", available on Bandcamp or wherever else you purchase and/or stream music from.

-

Sometimes known as the Spanish Flu, not because the flu originated in Spain, but because (neutral) Spain was the first to acknowledge it in their newspapers while countries such as the US and England who were embroiled in World War I censored their news so as to not damage morale.

-

Bernice Wuethrich, “Catching the Fickle Swine Flu,” Science, 7 March 2003, p. 1502.

-

Carol R. Byerly, Fever of War: The Influenza Epidemic and the U.S. Army During World War I (New York: New York University Press, 2005), p. 8.

-

Ibid., p. 92.

-

Donald G. McNeil Jr., “In New Theory, Swine Flu Started in Asia, Not Mexico,” New York Times, 24 June 2009, p. A11.

-

Linda Diebel, “Mexican Outbreak is Really ‘NAFTA Flu,’ Critics Say,” Toronto Star, 1 May 2009, p. A1.

-

Michael Greger, Bird Flu: A Virus of Our Own Hatching (New York: Lantern Books, 2006), p. 216.

-

Ibid., p. 37.

-

Ibid., pp. xv, 15.

-

Karl Drlica and David S. Perlin, Antibiotic Resistance: Understanding and Responding to an Emerging Crisis (Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: FT Press, 2011), p. 171.

-

Greger, Bird Flu, p. 305.

-

Quoted in Ibid., p. 306.

-

Paul R. Ehrlich and Anne H. Ehrlich, The Population Explosion (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1990), p. 143.

-

Greger, Bird Flu, p. 203.

-

Quoted in Ibid., p. 149.

-

Ibid., p. 113.

-

Ibid., p. 185.

-

Michael Greger, “10 Things You Didn’t Know About Bird Flu,” The Ecologist, February 2009, p. 27.

-

Thomas Walkom, “Pigs, Viruses and Politics,” Toronto Star, 2 May 2009, pp. IN1/IN5.

-

Paul Waldie and Grant Robertson, “Flu Inc.: How Vaccines Became Big Business,” Globe and Mail, 30 December 2009, p. B1.

-

David Waltner-Toews, The Chickens Fight Back: Pandemic Panics and Deadly Diseases that Jump from Animals to Humans (Toronto: Greystone Books, 2007), p. 10.

-

Drlica and Perlin, Antibiotic Resistance, p. 170.

-

“Shot to the System,” Maclean’s, 29 March 2010, p. 11.

-

I think I should point out here the wariness I have with one aspect of Greger's book, and that's his repeated support of the antiviral drug Tamiflu. I was kind of weirded out by its being portrayed as some kind of magical cure, and then was definitely weirded out upon learning that it's strictly made by only one company, a sure way to reek of disease profiteering. My suspicions were confirmed when I later read in Naomi Klein's book The Shock Doctrine and others that not only has the drug been severely hyped up and resulted in many serious side effects (including dozens of deaths), but much like other antivirals which have been broadly fed to chickens and which have become useless due to built up resistance, much Tamiflu resistance is emerging as well (Drlica and Perlin, Antibiotic Resistance, pp. 168-170). Furthermore, former US Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld was not only on the board of Gilead Sciences which created the drug, but even maintained stocks in the company while the administration he worked for made plans to purchase set quantities of the drug which thus earned him several million dollars.

-

Greger, Bird Flu, p. 344.

-

Ibid., p. 170.

-

Ibid., pp. 347-348.

-

Ibid., pp. 168, 194-196.

-

Ibid., pp. 180, 194.

-

Ibid., p. 194.

-

Ibid., p. 217.

-

Mike Davis, The Monster at Our Door: The Global Threat of Avian Flu (New York: The New Press, 2005), p. 108.

-

Michael Pollan, The Omnivore’s Dilemma: A Natural History of Four Meals (New York: The Penguin Press, 2006), pp. 171-172.

-

Thomas F. Pawlick, The War in the Country: How the Fight to Save Rural Life Will Shape Our Future (Toronto: Greystone Books, 2009), p. 66.

-

Ibid., p. 54.

Comments